Exploring how quality data leads to better information

Data and information, although used interchangeably, have different meanings and implications on the quality of health care. This article will cover the following:

- The definition of these concepts

- The distinction between data and information quality

- The impact of these on health care

- Health information professionals’ opinions on the treatment of health data

According to Oxford Languages, data refers to “facts and statistics collected together for reference or analysis.” Information is the product of processed data; this article defines it as “any amount of data, code or text that is stored, sent, received or manipulated in any medium.”

Differences between data and information

| Data | Information |

|---|---|

| Raw data | Processed data |

| Has little significance/meaning | Is meaningful and readily usable |

| Not organized | Clearly organized to aid decision-making |

| Can be stored in binary digits of 1 or 0 | Can’t be stored in binary digits of 1 or 0 |

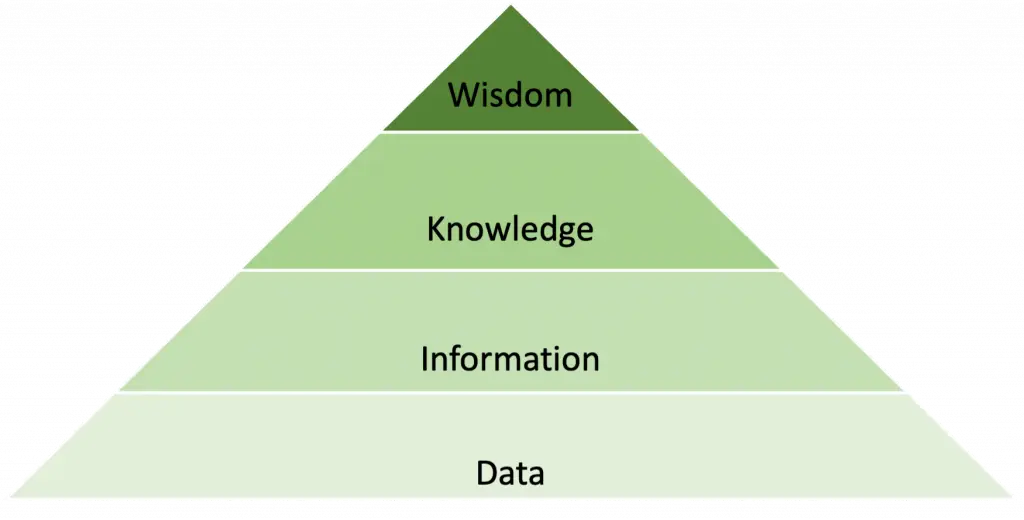

The Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) Pyramid is one model that explains data transformation: data is first converted into information, then it becomes knowledge that can be applied towards the future—wisdom.

There are differing opinions regarding the construct of this model and definitions within. For example, David Weinberger wrote via the Harvard Business Review that, “[Knowledge] results from a far more complex process that is social, goal-driven, contextual, and culturally-bound.”

Do you feel the DIKW Pyramid is relevant today? Why or why not?

Data and information quality

Data quality in health care is the ability of a set of data (such as demographic and clinical data) to provide the required information to meet the user’s needs (e.g., a research study using clinical data or a population health approach using the demographics). It is being able to rely on the accuracy, validity, cohesiveness, timeliness, and uniqueness of data to assess a health situation and provide quality health care.

What then is information quality? According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), it is the “quality of the statistics, indicators, analytical reports, electronic reporting tools and other information products” to determine patients’ needs.

In simple terms, data quality refers to the quality of the “raw” materials used to determine health care quality. In contrast, information quality refers to the quality of the refined products used to determine the same.

What are the implications of this on health care?

The treatment of health data and the preservation of their quality is a shared responsibility among all who handle them. Patients must be aware of their roles as data stewards and ensure accuracy and security in managing their data. Health information professionals must continuously develop their skills to keep up with trends in the health information landscape.

As data transforms into information, the impact on the patient, family member, clinician, or policymaker must remain at the fore.

CIHI’S data and information quality frameworks

CIHI’s 2009 Data Quality Framework consists of three components:

- A data quality work cycle (involving planning, implementing, and accessing)

- A data quality assessment tool (comprising of 5 dimensions, 19 characteristics, and 61 criteria)

- Documentation about data quality

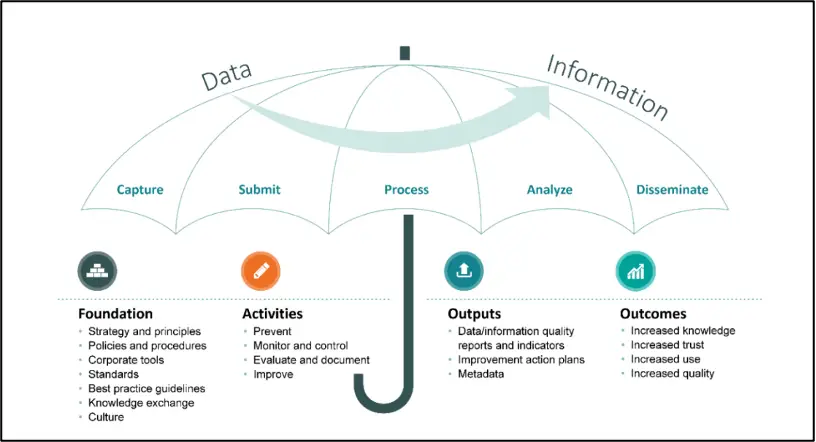

The 2017 CIHI Information Quality Framework is adapted from the General Statistical Business Process Model and presents a “holistic framework that encompasses and draws together a range of processes, practices, and tools.” This framework replaces the data quality framework. In the information quality framework, data transforms into information through steps (capture, submit, process, analyze, and disseminate) and aspects of quality management (foundation, activities, outputs, and outcomes). The framework is represented below.

The treatment of health data: Processes and silos

For Eley Wisniewski, information controller at Hamilton Health Sciences (HHS), when it comes to the distinctions between data and information quality, the difference is in what the data is as it transforms into information. Eley says the focus is on the quality of the data element and not on the quality of the information interpreted—the abstract’s completeness.

At HHS, Eley says data refinement is done as the data travels through several health information departments. For instance, while her team compiles data elements, reconciling and refining them to capture important details, the decision support team processes the data to refine care plans and prepare presentations to decision-makers. “We compartmentalize our roles here … All of our coders are CHIM professionals [sic]; they have to be, or I can’t hire them.”

As national conversations deepen regarding the variations in the treatment of health data and health information silos, Eley says that the road to universal standards in data handling is “a long time coming.” However, she suggested some solutions to enable the profession to effect changes in the delivery of care:

- Investment in good coders

- Collaboration with education programs to prepare students for real-life situations

- Investment in coding teams

- Oversight of coding teams

- Commitment to ongoing education for coders

- Development of clinical documentation improvement strategies

Data quality in a pandemic: Implications for health information professionals

Naomi Buchanan, a member of our Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island (NSPE) chapter committee, shared some insights on data quality in Canada during the pandemic. In her role as a data integrity officer with Nova Scotia Health (NSH), she ensures that that the information in their booking system is clean and adequately transferred to the provincial database.

She believes the pandemic has changed things for the profession, saying there is a greater need for more accurate data collection, mainly because of the “the public microscope” on the information health data officers provide. The consumption of health data no longer resides with health care professionals reviewing the data but now includes the end-users—the public.

Although there is a greater demand for greater transparency and accuracy in health data due to the pandemic, Naomi believes that health information professionals’ unique skills and education have prepared them for this moment.

Join us from Jan 24 to 28, 2022, for Data and Information Quality Week as we discuss the impact of the pandemic on data quality in Canada and strategies to advance the health information profession. There will be live events and professional development offerings during the week. Subscribe to our newsletter to get updates on the latest news from CHIMA about this awareness week.

Sources

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2009). The CIHI Data Quality Framework. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/dq-data_quality_framework_2009_en.pdf

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2017). CIHI’s Information Quality Framework. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/iqf-summary-july-26-2017-en-web_0.pdf

Folio3. (2021, November 16). What is the Importance of Data Quality in Healthcare Information Systems? Digital Health https://digitalhealth.folio3.com/blog/importance-of-data-quality-in-healthcare/

Oxford Languages. (n.d). Data. Lexico. https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/data.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2012). Information. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/information/

Weinberger, D. (2010, February 2). The Problem with the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom Hierarchy. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2010/02/data-is-to-info-as-info-is-not